SOLITAIRE

(translation)

This building beneath a London viaduct could hardly be more unusual — and once again raises the question: How much space do you really need to live large?

Photos: Taran Wilku | Text: Taran Wilku / AG

GOOD STORY — ENGLAND

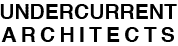

Beneath the arch of a railway viaduct in south London stands a building that demands attention: rust-colored corten steel panels, sharp edges, narrow windows, and slim light slits define its distinctive façade.

Archway Studios exemplifies how derelict urban voids can be transformed into vibrant spaces for living and working. The project was designed by Undercurrent Architects, founded in 2004 by Didier Ryan who set out to make a statement.

Where others saw only noise, confinement, and darkness, Ryan and his team saw potential.

“Small and difficult plots offer many opportunities,” says the architect, who completed the building in 2012 and moved in himself.

More than 10,000 of these Victorian railway arches still shape London’s urban fabric. Built in the early 19th century, they were rarely utilized and often neglected. Ryan found their constraints inspiring rather than limiting.

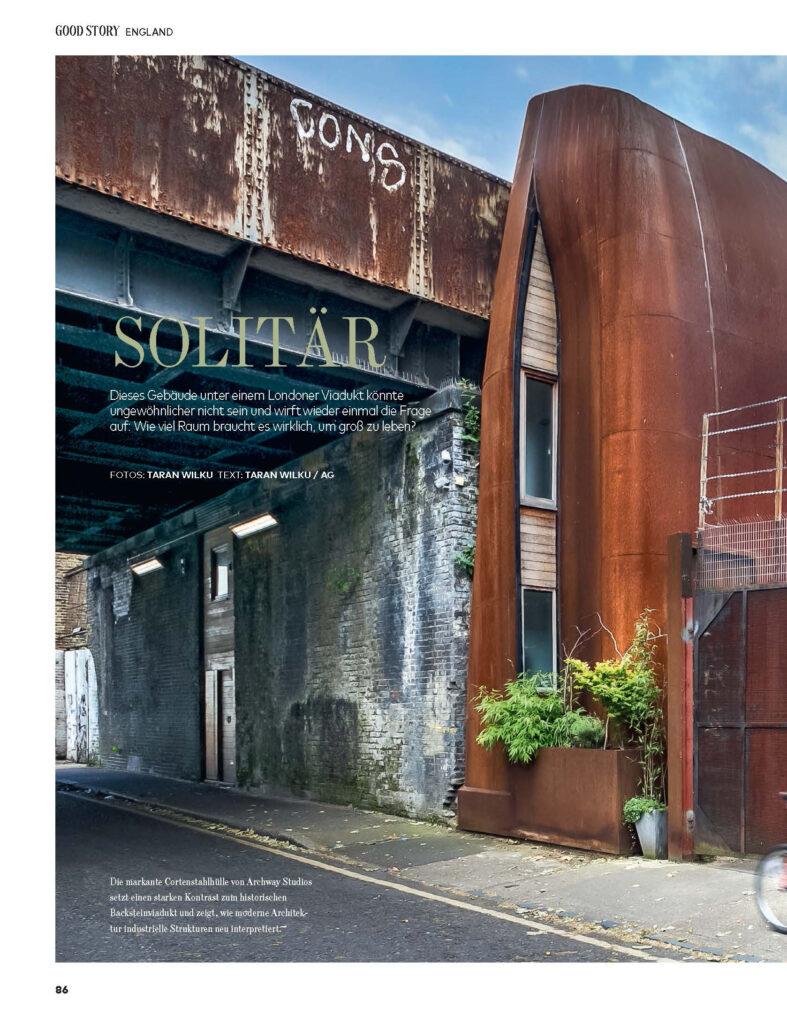

His design unites living and working on an exceptionally compact footprint.

“The greatest challenge was expanding the narrow layout and bringing light into the interior,” he explains.

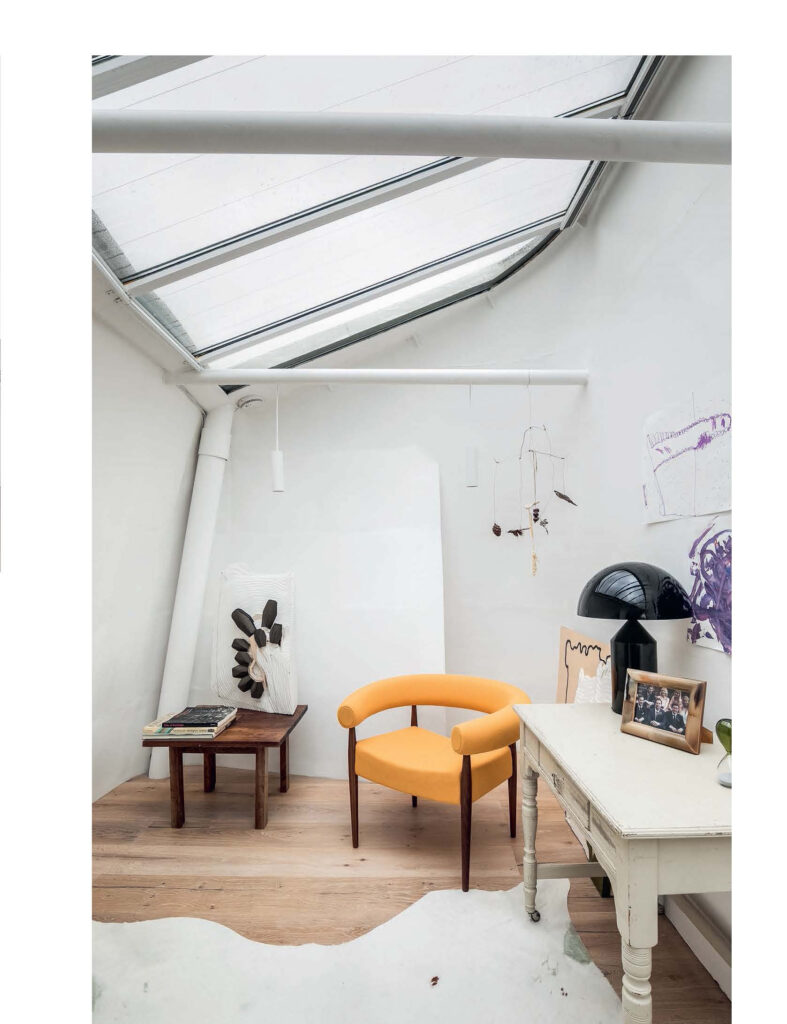

The solution: side windows and a rear extension with skylights that flood the space with daylight. The thick corten steel shell shields the interior from the noise and vibrations of passing trains while referencing the area’s industrial past.

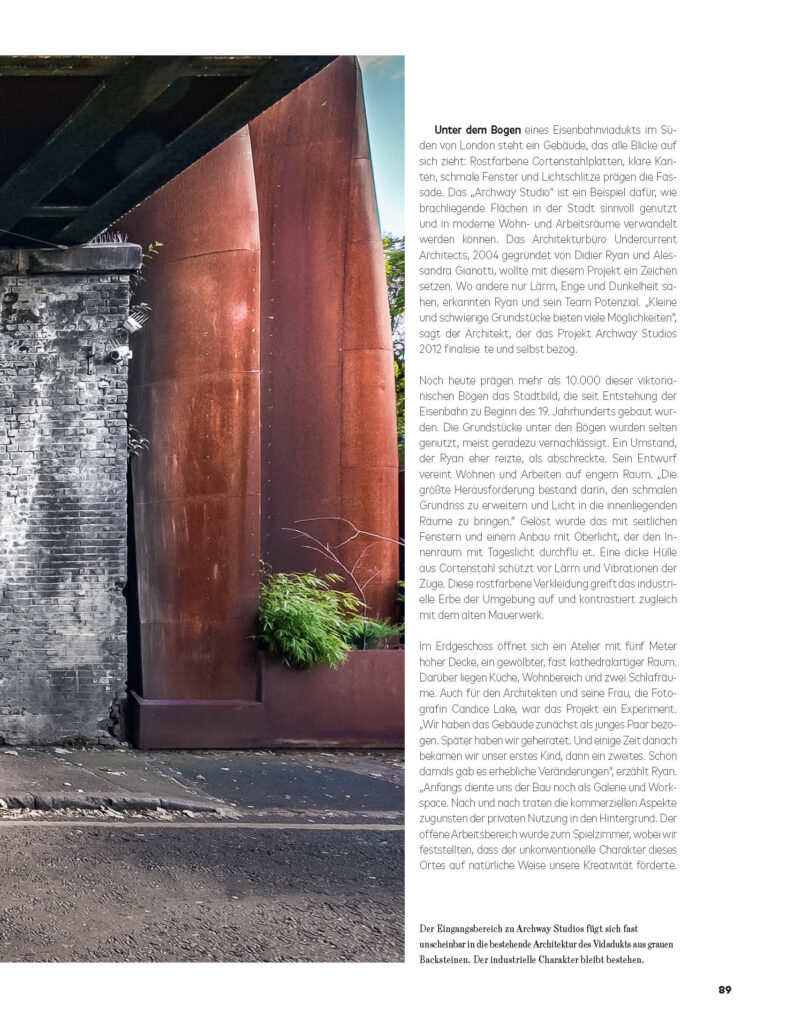

On the ground floor, a studio unfolds beneath a five-meter-high vaulted ceiling — a space almost cathedral in feel. Above are the kitchen, living area, and two bedrooms.

For Ryan and his wife, photographer Candice Lake, the project became a deeply personal experiment.

“We moved in as a young couple, then got married, and later had our first child — then a second. Even then, the house kept evolving,” Ryan recalls.

“At first it was a gallery and workspace. Over time, the commercial function gave way to family life. The open studio became a playroom, and we realized that the unconventional nature of the place naturally nurtured creativity.”

The entrance to Archway Studios blends almost seamlessly into the gray-brick viaduct — the industrial character intact.

“The railway became part of everyday life. The house lived with the rhythm of the city.”

— Didier Ryan

A Growing Family and Global Attention

As time went on, the family outgrew the space — three children, two bedrooms — and eventually moved out. But the memories of life in the studio remain vivid.

The project, however, took on a life of its own.

“It was fascinating to see how a small building, hidden in a hard-to-find London side street, could resonate globally,” says Ryan.

In post-industrial cities facing similar spatial and infrastructural challenges, Archway Studios became a model.

“It was a forerunner for a series of projects focused on reviving viaducts and unused infrastructure,” Ryan explains. “It helped spur initiatives like the Low Line and Spa Terminus. It showed people what was possible.”

In 2013, the building won the New London Architecture Award for London House of the Year.

“After that, we chose to move away from railway-arch projects so we wouldn’t get stuck in a niche,” Ryan adds.

Overcoming Resistance

Archway Studios is an architectural statement — but its realization was far from easy.

“There were countless obstacles,” Ryan remembers. “From skeptical neighbors and council officials to railway operators and property managers — everyone resisted change. On the construction side, no one wanted to deal with such a sculptural form. Building on such a tiny site felt like performing keyhole surgery. Every step was a battle against inertia.”

Inside, the contrast between the bright, open interior and the rugged industrial shell is striking. Iconic furniture pieces — such as Moroso’s Shadowy chair and Gebrüder Thonet Vienna’s burgundy Targa armchair — echo the viaduct’s curved forms.

While the bathrooms, bedrooms, and kitchen are compact, the lofty studio beneath its dramatic vault feels open and uplifting — an inspiring setting for creative work.

Lessons and Legacy

Only after the project received recognition did early opposition turn into support. The experience deeply influenced Ryan’s philosophy:

“No matter the obstacles, it’s important to keep moving forward. Involve people, stay open, and use your influence to help others.”

Looking back, he would change little about the design.

“Rather than making major changes, I’d focus on refinements. The building still works beautifully and has proven remarkably adaptable. If anything, I’d integrate more sustainable systems, which are now far more accessible. But I’d remain true to the spirit of experimentation and creativity that comes from working within limits.”

Ryan still sees potential in these unconventional spaces — though not without challenges.

“A major issue is that these properties are often leased short-term, mainly as workspaces. That prevents long-term residential or community use. Without changes to policy or leasing structures, possibilities remain limited. But as London and other cities continue to grow, new infrastructure — and new viaducts — will open opportunities for integrated, lasting uses.”

Conclusion

In a city where space is scarce and historic structures often stand in the way of progress, Archway Studios offers a compelling vision for the future. It shows how neglected urban pockets can be transformed into functional, contemporary spaces — and proves that architecture often draws its greatest strength from constraint.